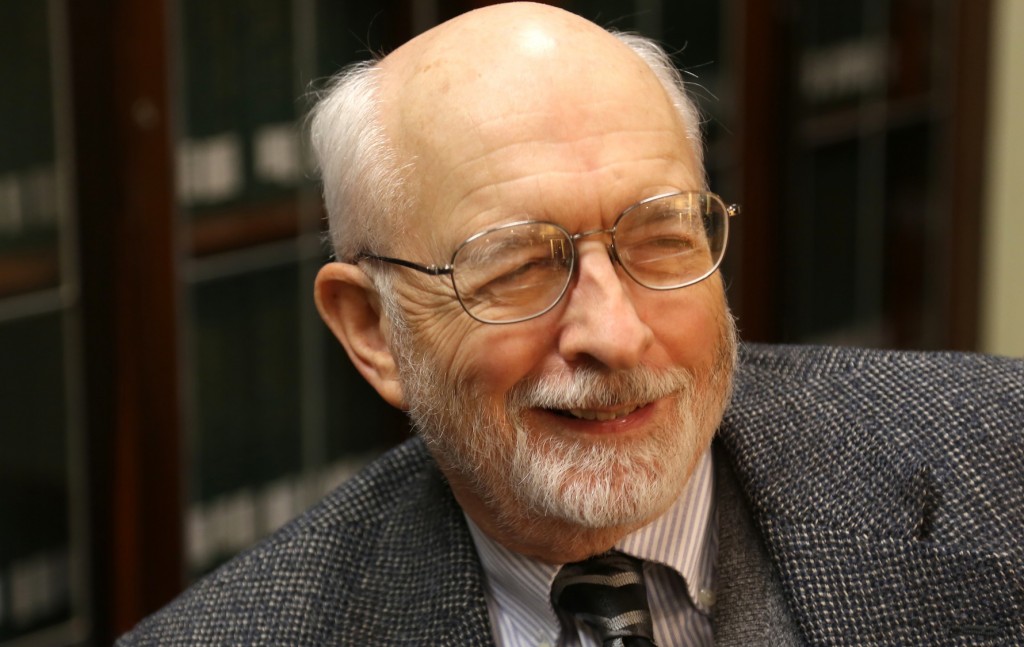

Bob Baird, Chair of Task Force

Dr. Robert Baird, Professor and Master Teacher, has been part of BIC since before BIC even started and has taught in the philosophy department since 1968. After this semester Dr. Baird will retire, so we were pleased to honor him and another retiring BIC professor, Dr. David Longfellow, at this year’s Senior Recognition Banquet. Both Dr. Baird and Dr. Longfellow offered reflections on their time spent in BIC. Dr. Baird chose to reflect on the beginnings of BIC, and he has graciously allowed us to post his comments here. I hope you enjoy. (You may also want to read an article about Dr. Baird at the Arts & Sciences Blog)

————————–

Remarks to BIC Graduating Seniors

April 15, 2014

Robert Baird

There is a story to tell about the creation of BIC. There is even a story behind the story (a back story) to the creation of BIC. And since I am retiring, about to pass off the scene as it were, and since I chaired the task force that created the BIC, I decided that what I should do here as a final farewell to you students graduating in the BIC is to briefly tell that story.

On a January afternoon in a year before most of you were born, January 1991, I received a phone call from a secretary telling me that the vice president for academic affairs, Don Schmeltekopf, and the Dean of Arts and Sciences, Bill Cooper, wanted to come to my office to visit with me.

That meant one of two things: they were going to fire me or ask me to do something so big that they were willing to come to my office and it was going to take two of them to lay the task on me.

Well, the task was big—it was to chair a group of faculty that would have two responsibilities: to create an interdisciplinary core program so comprehensive that any Baylor student could be a part of it, no matter the college the student was in—arts and sciences, business, music, or, education. There was no school of engineering at the time. The second task was in some ways even more daunting—to get the Baylor faculty to buy into it, to approve an interdisciplinary core.

Here is part of the back story. In the mid-1980s four major national studies of undergraduate education in the United States were released. All four emphasized the need for colleges and universities to reexamine their core curricula and called for a commitment to interdisciplinary teaching and learning.

During the 1984-86 University Self-Study, the undergraduate curriculum committee influenced by those four national reports called for reexamination of Baylor’s core curriculum and for a more interdisciplinary core.

Now, back to the main story.

I agreed to chair the task force and the vice president proceeded to appoint 20 additional members. Most of those individuals are no longer at Baylor, some have retired, some moved on to other universities, and several, in fact, have now died.

Some are still teaching or recently retired. You know many of them: Bill Bellinger, chair of the religion department, Ray Cannon, who retired last year and who taught in World III from the beginning, Tom Hanks who has been a part of the World Cultures courses from the start, and Larry Lyon, now dean of the graduate school.

The task force was to begin its work in the fall of 1991, but before we actually met the President of the University, Herb Reynolds, who was thoroughly on board with the project, sent me to a meeting at Yale University where reports from all over the country were being made by universities that had attempted such a comprehensive, interdisciplinary core. The meeting was frightening. Report after report was a report of failure. And it seemed clear to me that the failure was the direct result of a committee or task force being formed that then in isolation created a program and, in effect, sprang it on the faculty—and faculty after faculty said “no”.

With considerable concern I returned to Baylor, reported this to the Baylor task force, and our unanimous thought was that if we did not enter into a campus-wide conversation with the faculty from the get-go, if we did not make the larger faculty a vital part of the process, the whole endeavor was doomed.

So in the fall of 1991, the task force entered into a university-wide conversation about the goals of such an interdisciplinary core. The members of the task force met multiple times with the faculty of every department, and by the end of the fall a written statement of goals was completed and mailed out to the faculty. Critiqued by the faculty, revised by the task force, in the spring of 1992 those goals were redistributed to the faculty and became our guideline.

We had taken almost a year; we did not have a core curriculum, but we did have a set of goals, and more importantly, we had faculty from every corner of the university involved in the process.

In the summer and fall of 1992, in meeting after meeting for seven months, we hammered out a draft of the BIC.

Then for three months in 1993, January, February and March, we held public hearings on the proposal. The task force met with individuals and with groups who expressed their views—pro and con.

The most widely expressed objection was that only a Shakespearian scholar should teach students the plays of Shakespeare; only a historian should read and discuss with students documents related to the French Revolution; only a philosopher should engage students in the thought of Plato.

The rejoinder we made to that argument was that perhaps students could profit greatly by having discussions with faculty who were not experts in every text being discussed, but who could model a non-expert grappling with the material. That response undergirded our basic argument for interdisciplinary work. When students graduate, when you graduate, you will not make decisions as a student of philosophy or Spanish or biology. You will make decisions as a human being, as a human being integrating all that you have learned. You will make interdisciplinary decisions.

Here is the end of the story. Not the end, of course. Here is the end of the beginning of BIC. In April of 1993 (almost two years after we had begun), our proposal was submitted to the faculty for a vote. The faculty of the college of arts and sciences met as a whole to discuss the proposal again, with pro and con arguments out on the floor again; then each member of the faculty of the college of arts and sciences was mailed a ballot and given ten days to respond. I must tell you in all honesty, when those ballots went out, I had no clue whether it would pass or fail.

Well you know and I now know it passed. But at the time I seriously did not know. But it passed: 72% for, 28% against—believe me, for a proposal that so controversial at the time, was an overwhelming endorsement. Separate approval was subsequently given by the schools of Business, Education, Nursing, and Music.

I am completing my 47th year on the Baylor Faculty. Many daunting tasks I faced during those 47 years. Few, maybe none, more daunting than helping to create the BIC. Few, maybe none, more important than my helping to create the BIC. Thanks to all of you for your investment in the BIC. And as you graduate, my best to you.